Chicago Redeye: South Side Proposals

The CTA’s recent announcement of various proposals for enhancing service along the South Lakefront Corridor is frustrating to say the least. Some of the proposals involve restoring service that was cut at various points in the past, like Green Line service beyond East 63rd/Cottage Grove and express bus service on King Drive. The King Drive proposal is notorious because it paints the agency as having bipolar tendencies that would go a long way toward alienating passengers. Riders will not take kindly to services disappearing and reappearing every few years. Unfortunately, the CTA is under the mistaken impression that they are the stars of another live-action adaptation of Brigadoon and they’re apparently okay with that.

Enhanced Bus Service: The CTA has proposed a new crosstown bus route on 83rd Street, in between existing bus routes on 79th Street and 87th Street. At first glance this appears to be a reasonable move considering the two aforementioned routes were ranked 15th and 1st for weekday traffic between 2001-2010 according to my research (this consisted of looking at bus routes that have run consistently and year-round since 2001). 79th Street has almost 33,000 weekday riders while 87th Street has almost 17,000; the question is how much additional demand is there to justify a bus route on 83rd Street. If the issue is one of insufficient capacity then additional buses could be added to 79th Street, but this would admittedly be difficult considering the frequency at which the CTA is currently running buses. Presently westbound buses can have head ways as short as three minutes, and additional buses would have to compete with automobile traffic. Despite these challenges, it would be wiser to improve service on existing corridors than pursuing the creation of new ones. A new bus route on a street with only two traffic lanes means that the buses act as pacing cars for the road; unless cars can get around buses while they are stopped for passengers the speed of all vehicles will be dictated by the need of the bus to travel slow enough to collect passengers. On an east-west street with 16 intersections per mile this speed can be as low as 5 miles per hour which is incredible inefficient from an energy perspective.

79th Street could be improved through the simple act of banning street parking, at least during rush hour so that buses could have unfettered access to the curb. Another solution could be the conversion of 79th Street into a bus rapid transit corridor. All stops could be built as curb extensions so buses would not have to pull over to pick up passengers; private vehicles would be banned during rush hour so buses could have exclusive use of the road. Delivery trucks and vehicles requiring curbside parking could still be allowed. however. There are many more possible implementations, but the primary goal would be to keep 79th Street sufficiently served by transit and eliminate the need for an additional crosstown bus route.

The proposal to restore express bus service on King Drive is quite irritating since all the express bus routes were eliminated during the last service reduction, the justification being that the CTA would save money. Route 3-King Drive was the 6th busiest bus route in terms of average weekday ridership over one month and 7th busiest in terms of total monthly usage according to my analysis. The X3 express route on the other hand only peaked at approximately 3,408 average weekday riders over one month (AWRM) between 2005 and 2009. Express service on King Drive was never popular to begin with, it’s maximum AWRM being only 13% of Route 3-King Drive’s (3,400 versus over 25,470) between 2005 and 2009. The desire to reinstate express service in this corridor is another example of the CTA’s skewed priorities.

Restoring express bus service to Western Avenue would make a lot more sense; average weekday riders over one month (AWRM) peaked at 17,328 on the express route while it was in operation compared to the regular route’s AWRM maximum of 27,456 for the same period. The express route’s maximum AWRM was over 63% of the regular route’s maximum AWRM which makes the decision to eliminate express service on Western Avenue quite hard to comprehend.

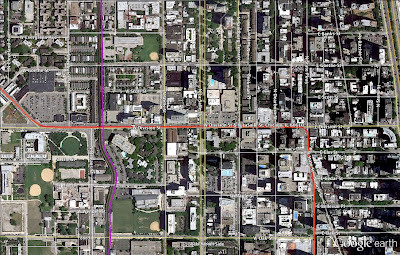

Rapid Transit: The CTA is proposing to extend the Green Line East 63rd/Cottage Grove Branch to Dorchester Avenue, which signals another U-turn by the transit agency. This portion of the Green Line was demolished during the renovation between 1994-1996 [1] due to community concerns about blight. The kicker is that the decision to abandon this portion of the line meant that the CTA was forced to forfeit federal funds. Now that they want to restore this portion its a safe bet that the USDOT will not be enthusiastic about federal funding for it. They did provide $384 million for the Cermak Branch of the Blue Line (now the Pink Line) but I maintain that that was done more for political reasons than operational necessity. Jackson Park is a major civic space on the South Side, and its presence is certainly justification for L service. It is quite confusing to hear people cite blight as a reason for demolishing a transit line, as a thorough renovation could have reversed that blight. Just because something is old doesn’t mean you tear it down; if people had followed that philosophy the CTA L would be a puny reminder of better days.

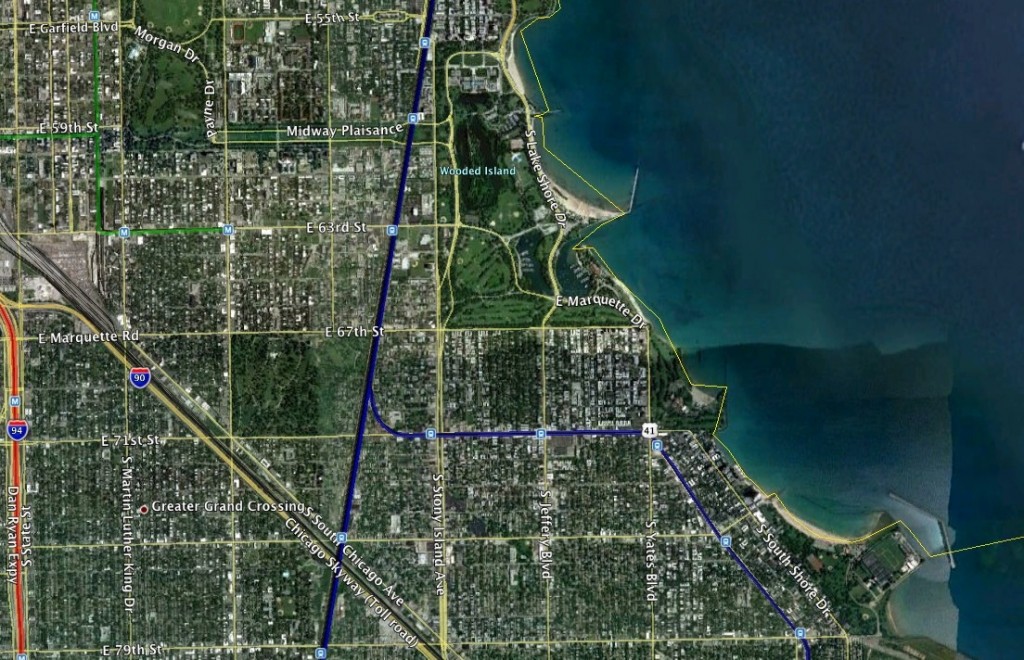

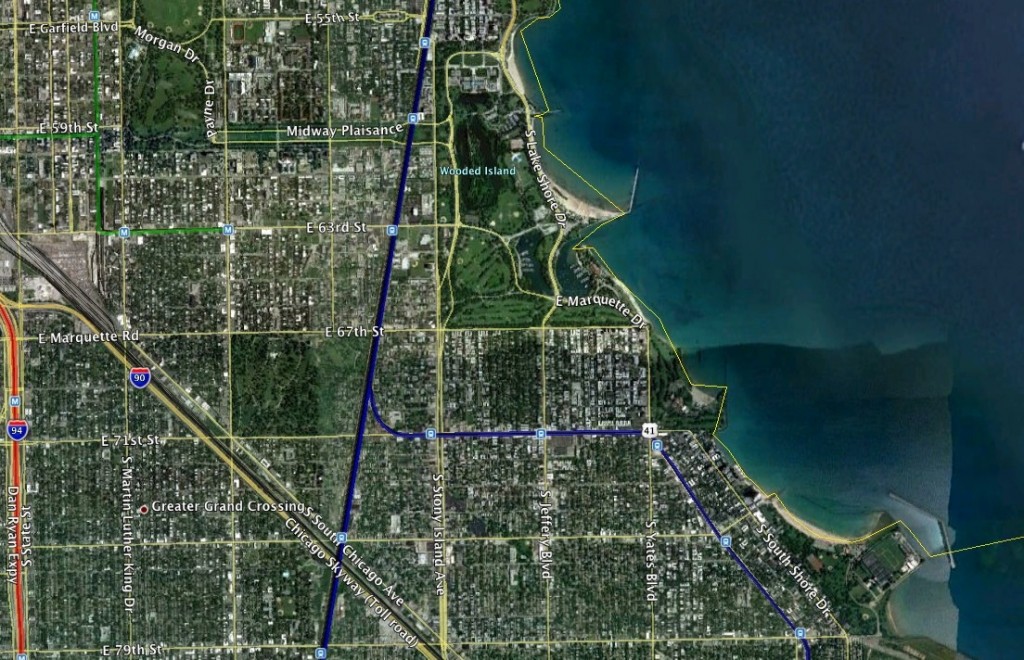

The overall issue is one of necessity: does Woodlawn have enough demand to justify reinstating Green Line service. An elevated transit line would be a large infrastructure improvement that could be replaced with enhanced bus service. Some have posited [2] that the opening of the Dan Ryan Line reduced the utility of the Jackson Park branch, leading to its demolition. This does bring up an important issue: the competition between the Green Line South Side Elevated and the Red Line Dan Ryan Branch. The main advantage that the Dan Ryan Branch has is its reach farther south compared to the Green Line, which means more riders. Having two lines competing for the same passengers is counterproductive; any bus going east stops at the Red Line first which undoubtably siphons off a lot of potential Green Line riders. The Green Line also competes against the South Lakeshore express buses that serve Hyde Park and other neighborhoods. The Metra Electric also serves the lakefront, and does a better job since it runs within a few blocks of the lake making it a lot more convenient; people taking the lakefront buses or Metra Electric do not have to transfer to another route to reach their lakefront destinations in Hyde Park, Woodlawn, or South Shore.

South Shore Trains

Bus Rapid Transit: The CTA is proposing a Bus Rapid Transit Corridor on Cottage Grove Avenue as well as 79th Street and Garfield Boulevard. Cottage Grove Avenue is well suited for bus rapid transit due to its generous width of four traffic lanes plus street parking. Unfortunately the analysis of X3-King Drive ridership seems to indicate that there is a lack of interest in express bus service in this corridor. Part of the problem is the presence of lakeshore express buses running from Hyde Park to the Loop. If one is heading all the way downtown from Kenwood, Woodlawn, Hyde Park, or South Shore the lakeshore express buses are a far more logical method of travel since they run express for 47th Street all the way to Roosevelt. Cottage Grove Avenue was served by the X4 Express bus in the past, and its ridership situation strongly mirrored the King Drive buses. The average monthly ridership over one month (AMRM) was about 2,892 from 2007 to the end of service in 2010 while the ridership on the regular 4-Cottage Grove bus was 22,162 over the same period which corresponds almost perfectly to King Drive when it had two buses: express AMRM was 13% of the regular route’s. If the CTA is insistent on bus rapid transit in this corridor, it would be wise to combine the King Drive and Cottage Grove BRT proposals. One possible way of doing this would be to implement a scheme similar to the Michigan Avenue-Indiana scheme where one road handles northbound and the other southbound. The Southbound BRT could run on King Drive and the Northbound BRT could run on Cottage Grove. This would reduce the impact of buses on traffic since only one lane would be used on each road instead of two. The CTA would be wise to explore similar implementations in other heavily used corridors since many Chicago thoroughfares are somewhat narrow (Ashland, Halsted and Broadway come to mind).

Another CTA proposal involves installation of equipment to give the 79th Street bus priority at traffic signals. This is very similar to my aforementioned proposal for BRT on this street. One difficulty that faces Chicago when it comes to implementing an idea like signal pre-emption is the technological lag in many areas. Numerous Chicago traffic signals still use electro-mechanical timers instead of solid state computers with road sensors. Upgrading the traffic signal technology on the major road corridors would be a positive but expensive step; a much cheaper way to speed up buses would be to relocate all bus stops to the side of the intersection past the signal so that buses do not get stuck at signals while discharging passengers. Another step would be to eliminate the acceptance of cash on buses and use farecards exclusively. Farecard machines would be installed at major points of commerce along 79th Street to facilitate this.

Integrating Metra:

Another plan involves running Metra trains more frequently in the lakefront Electric corridor and building a new station at 35th Street. There are multiple problems with the viability of such a proposal, mainly the fact that there are already better options for transporting people along the lakefront. The south lakefront express buses make very good time, with speeds approaching 30 miles per hour which rivals the Metra Electric. More importantly, Metra is very labor intensive since trains require an engineer and at least one conductor to collect fares from passengers.

Transforming Metra into a rapid transportation system from a commuter rail system would require a dramatic change in operations. One problem with implementing frequent service (10 to 15 minutes between trains) is the amount of rolling stock that would be required. The specific number of cars would depend on the current passenger demand pattern throughout the day. It could be possible to provide more frequent service with the current fleet by running shorter trains; shorter trains would allow more runs per hour but run the risk of stranding people on the platform for long periods of time due to crowding. There is another problem with shorter trains: longer trains would either have to be assembled when they are needed or kept in a ready state. Permanently assigning some trains to low frequency duty would reduce the number of short trains available for rush hour. This type of situation would be preferred by yard operators since it would cut down on the amount of coupling and switching that has to be done and keep more trains in revenue service.

It would probably be better to simply detach the Metra Electric corridor from the body of Metra and have the CTA assume responsibility for operations. Metra simply doesn’t have the experience of providing service at such high frequency. Implementing a fare card and turnstile system would be very difficult since Metra platforms aren’t really set up for it; a lot of the head houses are quite cramped and would only allow a few turnstiles. Turnstiles did exist in the Metra Electric corridor in the past, but the functioned more as access barriers rather than fare collection devices (tickets were still checked on the train). The CTA would also have to bring back conductors whom they eliminated when switching to one person train operation.

Whatever decisions the CTA makes regarding south lakefront transit, it needs to make sure it doesn’t reverse course after a year and undergo costly dismantling of its latest blunder.